India’s ECCE Journey

Over the past two decades, several national and international studies have repeatedly highlighted that a large proportion of children in India are enrolled in school but are not achieving expected levels of foundational learning. Research consistently points to early-grade reading and numeracy as the weakest areas. For instance, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) has, year after year, shown that many children in Grade 3 struggle to read a simple Grade 1 text or perform basic two-digit subtraction. Similarly, the National Achievement Survey (NAS) has reported significant learning gaps in language and mathematics at the primary level, indicating that children are moving to higher grades without mastering essential foundational skills. And all above are the result of an unbuild bridge from Policy to Practice in india’s ECCE journey

These findings align with global research as well. Studies by the World Bank and UNESCO describe this as a “learning poverty” challenge, where children are in school but unable to read with understanding by age 10. Research in early childhood education further shows that learning gaps appear as early as preschool, and if not addressed, they tend to widen with each passing year. Cognitive science studies also emphasise that strong language exposure, early numeracy experiences, and play-based learning in the 3–8 age group have long-term effects on academic performance and overall development.

From need identification to Policy formation in India’s ECCE Journey

While the 86th Constitutional Amendment (2002) revised Article 45 to focus on early childhood care and education (ECCE) acknowledging its importance, the education system did not witness any major nationwide reform in this area for several years. Anganwadi centres continued to focus more on nutrition and health, and primary schools often emphasised syllabus coverage rather than foundational skill-building. As a result, despite high enrolment levels, foundational learning remained weak.

This long-standing gap was finally recognised and addressed in the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, which placed Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) as the most urgent national priority. The policy explicitly states that without strong foundations by Grade 3, the entire school journey becomes challenging for a child. NEP 2020 brings ECCE and FLN together as a single continuous stage, fulfilling the true intent of Article 45 and shifting India’s focus towards strengthening the earliest years of learning.

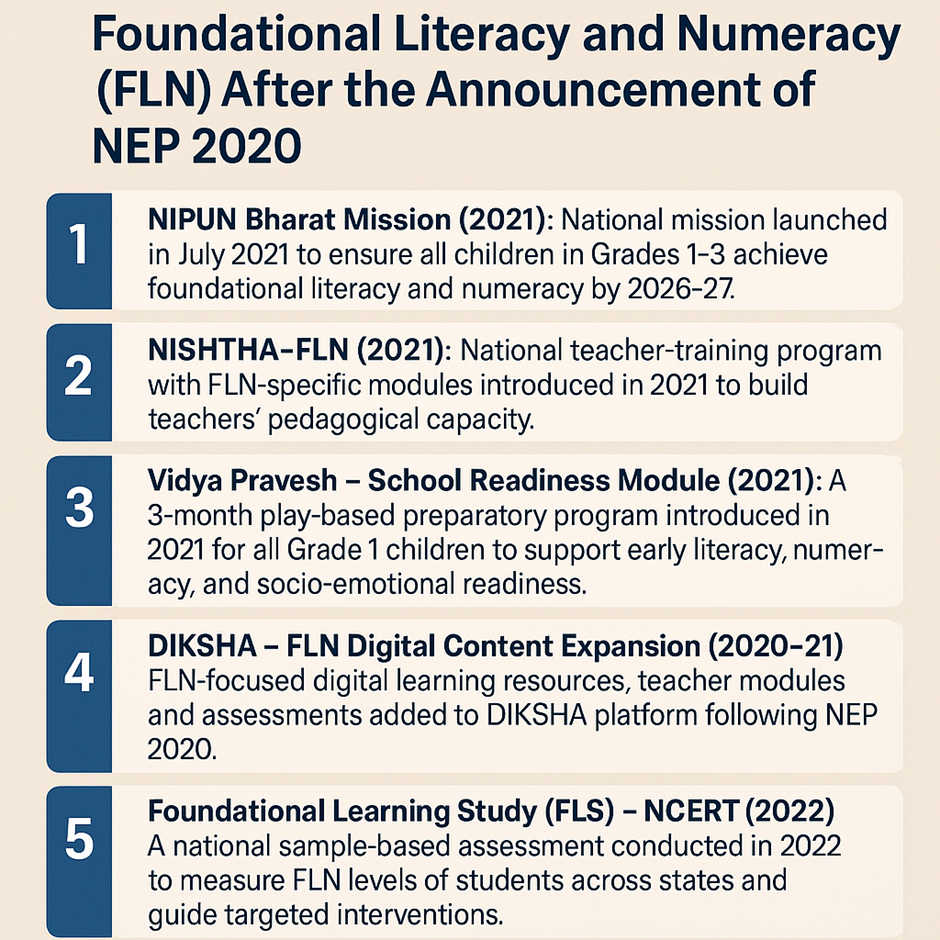

Initiatives for Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) After NEP 2020 (Milestones in India’s ECCE Journey)

When the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 came out, it made one thing very clear: every child must learn to read with understanding and develop basic number skills in the early years. This is the foundation of all future learning.

To make this happen, the Government of India started several programmes after NEP 2020. Each programme focuses on helping young children learn better and making sure teachers have the right support and tools.

Here are the major initiatives explained in simple language:

1. NIPUN Bharat Mission (2021)

NIPUN Bharat is the main national mission started in 2021.

Its aim is simple: by 2026–27, every child in Grades 1–3 should be able to read fluently and do basic maths confidently.

The mission encourages fun and meaningful learning—through activities, play, stories, hands-on tasks, and tracking each child’s progress. States prepare their own plans so that the mission reaches every school and every child.

2. NISHTHA–FLN (2021)

Good learning begins with confident and well-trained teachers.

So, in 2021, special FLN training was added under the NISHTHA programme.

These training modules help teachers understand:

- how to teach reading in simple steps,

- how to build number sense,

- how to use children’s home language effectively, and

- how to assess learning without stressing children.

Millions of teachers across the country have taken this training.

3. Vidya Pravesh – School Readiness Programme (2021)

Not all children attend preschool. Many enter Grade 1 without early exposure to stories, conversations or structured learning.

To help them start smoothly, Vidya Pravesh was launched in 2021.

It is a 3-month fun, play-based programme that builds:

- early language skills,

- simple pre-math skills,

- social and emotional confidence.

This helps children feel ready and comfortable before formal learning begins.

4. DIKSHA – FLN Digital Resources (2020–21)

After NEP 2020, DIKSHA was strengthened with thousands of FLN materials.

Teachers can now access:

- short videos,

- worksheets,

- stories,

- activities, and

- reading and maths practice material.

Everything is available in many Indian languages.

This makes good-quality resources available even in remote areas.

5. Foundational Learning Study (2022)

In 2022, NCERT carried out a large study to understand how well children across India were learning to read and do basic maths.

This study shows:

- where children are doing well,

- where gaps exist,

- and what kind of help schools need.

The findings guide the government and states in planning the next steps for FLN.

6. State-Level FLN Initiatives (2021 onwards)

After NEP 2020 and NIPUN Bharat, almost every state started its own FLN programme.

For example:

- Mission Prerna (UP)

- NIPUN Haryana

- Mission Ankur (MP)

- Nipun Axom (Assam)

- Mission Buniyaad (Delhi & Rajasthan)

- FLN programmes in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, etc.

Each state uses its own approach, language support, training methods and community mobilisation strategies — but the goal everywhere is the same: helping every child build strong foundational skills.

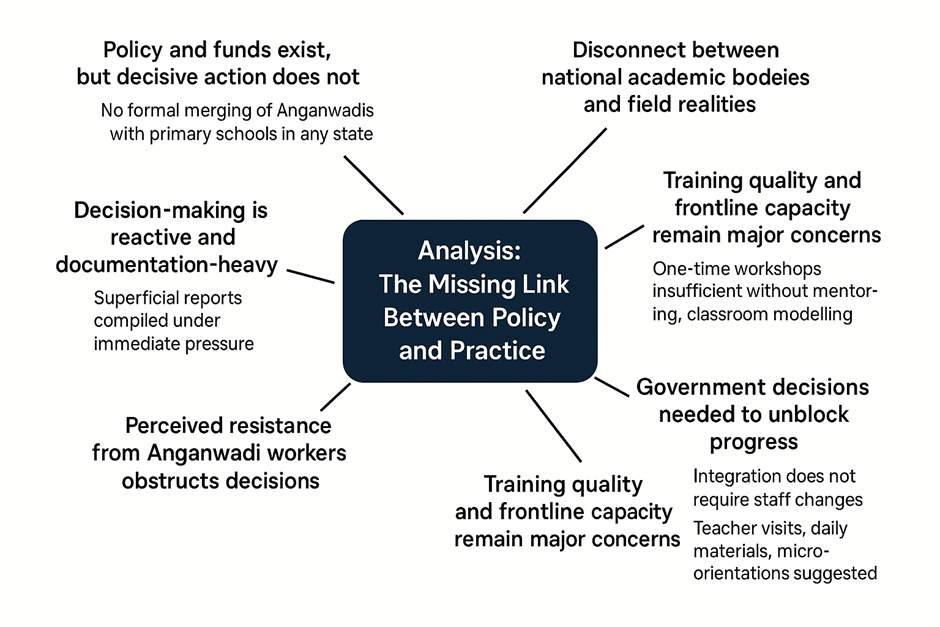

The Missing Link Between Policy and Practice

1. Policy and funds exist, but decisive action does not.

- NEP 2020 prioritises FLN and ECCE, and funds are available under Samagra Shiksha.

- Yet no state has formally announced the merging or academic integration of Anganwadis with lower primary schools.

- Centre and states keep shifting responsibility: states wait for central orders, and the

- Centre only demands reports instead of giving clear directions.

- Administrative action often happens only when a political question is raised in Parliament, causing rushed paperwork rather than meaningful reform.

2. Decision-making is reactive and documentation-heavy.

- When pressure comes from above, states hurriedly compile reports through junior officials who often lack field insights.

- This results in superficial documents created in a few hours, while genuine ground-level planning remains weak.

- Daily functioning remains unchanged, and the system returns to its old pace once the immediate pressure passes.

3. Perceived resistance from Anganwadi workers obstructs decisions.

- States often claim that Anganwadi workers may oppose merging or restructuring due to job concerns.

- As a result, decisions are avoided instead of addressing the concerns through dialogue, clarity, or phased implementation.

- This fear becomes a convenient excuse to delay structural reforms.

4. Disconnect between national academic bodies and field realities.

- NCERT continues to develop ECCE content and guidelines, but often without real-time insights from field practitioners.

- This risks creating material that is academically sound but not practically relevant.

- The gap between “policy intention” and “classroom reality” remains large.

5. Training quality and frontline capacity remain major concerns.

- During one of my training sessions (location not disclosed intentionally), interactions with five Anganwadi workers revealed critical gaps.

- They did not know what a curriculum is, were unsure why they were invited, and were unfamiliar with basic ECCE terminology.

- Their willingness to learn was high, but the system has never provided them with continuous mentoring or real classroom demonstrations.

- This shows that one-time training packages are insufficient without regular academic support.

6. Government decisions are needed to unblock progress.

- Integration of ECCE and early grades does not require staff changes—only coordinated planning.

- Simple steps could make a big difference:

- weekly teacher visits to Anganwadis,

- daily learning materials for ECCE centres,

- micro-orientations instead of long, ineffective training packages,

- joint planning between Anganwadi workers and teachers.

- Without structural decisions, funds risk being underutilised and promises remain symbolic.

7. If NEP could be implemented nationally, ECCE–primary integration is also possible.

- The Centre demonstrated strong willpower in implementing NEP 2020.

- A similar level of clarity and direction can easily guide states to integrate ECCE and primary education systems.

- This would reduce confusion, strengthen foundational learning, and support India’s long-term FLN goals.

Conclusion

India’s commitment to strengthening Foundational Literacy and Numeracy after NEP 2020 marks a major step forward, but the journey from policy to real classroom change is still unfolding. While national missions, guidelines, and funding have created a strong foundation, the real impact will depend on consistent decisions, stronger coordination, and practical action at the ground level. The early years are too important to leave to fragmented efforts or delayed reforms. With the right direction and support, India can bridge the gap between policy and practice and create meaningful learning experiences for every young child.

In my next article, I will share what can be done academically for ECCE—simple, practical, and research-based steps that can genuinely improve early learning in Anganwadis and primary schools.

References

ASER (Pratham). (2023). Annual Status of Education Report. Pratham Education Foundation. https://www.asercentre.org

Central Board of Secondary Education. (2021). National Achievement Survey 2021. Ministry of Education, Government of India. https://nas.gov.in

Ministry of Education. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. Government of India. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

UNESCO. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.unesco.org/en/education/gem-report

World Bank & UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2021). India Learning Poverty Brief. World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/943181624930019557/india-learning-poverty-brief-2021

Government of India. (2002). The Constitution (Eighty-Sixth Amendment) Act, 2002. Ministry of Law and Justice. https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-sixty-eighth-amendment-act-2002

Government of India. (2009). The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. Ministry of Law and Justice. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/rte.pdf

NCERT. (2022). Foundational Learning Study 2022. National Council of Educational Research and Training. https://ncert.nic.in

NCERT. (2021). NIPUN Bharat: FLN Mission Implementation Guidelines. Ministry of Education. https://dsel.education.gov.in/nipunbharat

NCERT. (2020). Learning Outcomes at the Primary Stage. National Council of Educational Research and Training. https://ncert.nic.in/pdf

UNICEF India. (2022). Early Childhood Education and FLN Briefs. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/india

NIPCCD. (2021). Early Childhood Care and Education Position Paper. National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development. https://www.nipccd.nic.in

Rajni is an accomplished education professional who holds a PhD in Education and MPhil and MA degrees in Economics. She has extensive experience in research, having published over 16 research articles in peer-reviewed journals and contributed to articles in an edited book. Additionally, Rajni has authored a book in the field of education.

Rajni is passionate about making a difference in the field of education. She is an aspirant who is eager to do something innovative and valuable and is constantly striving towards creating a positive impact. She believes that education is a powerful tool which can change lives and that every student deserves access to quality education.

Rajni has a strong work ethic and a deep commitment to her profession. She is driven by her passion to learn, explore and contribute to the growth of the education sector. Her knowledge and experience in Economics and Education, combined with her intellectual curiosity and research skills, place her in a unique position to push the boundaries and creatively tackle complex challenges in the education field.

Overall, Rajni is an accomplished and driven professional who is poised to continue making a meaningful contribution in the field of education.